Berkeley second dialogue summary. Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous: Summary 2023-01-04

Berkeley second dialogue summary

Rating:

9,3/10

1843

reviews

The Berkeley Second Dialogue, also known as the Second Dialogue on Human Nature, is a philosophical work written by George Berkeley in 1713. The dialogue is a continuation of Berkeley's first dialogue, which dealt with the nature of perception and the existence of matter. In the Second Dialogue, Berkeley expands upon his ideas about the nature of perception and the role of the mind in constructing reality.

Berkeley begins the Second Dialogue by addressing the objections raised by his previous dialogue, in which he argued that material objects do not exist independently of the mind. He asserts that this position, known as immaterialism, is not as absurd as it may seem at first glance. He argues that the common sense notion of material objects as independently existing entities is based on a misunderstanding of the nature of perception.

According to Berkeley, our perception of material objects is not a direct representation of the objects themselves, but rather a result of the mind interpreting sensory data. In other words, our experience of the world is not a direct representation of the physical world, but rather a construct of the mind.

Berkeley argues that this constructivist view of perception has important implications for our understanding of the nature of reality. He contends that the material world does not exist independently of the mind, but rather is a product of the mind's perception and interpretation of sensory data. In this sense, reality is not an objective, independently existing entity, but rather a subjective construction of the mind.

Berkeley's immaterialist position has been a source of much debate and criticism among philosophers. Some have argued that his position leads to a number of paradoxes and contradictions, while others have defended it as a coherent and viable alternative to the traditional materialist view of reality.

In conclusion, the Berkeley Second Dialogue is a philosophical work that explores the nature of perception and the role of the mind in constructing reality. Berkeley's immaterialist view of reality has been a source of much discussion and debate, and continues to be an important and influential idea in philosophy.

Analysis Of Berkeley's Three Dialogues Between Hylas And...

And, hath it not been made evident that no such substance can possibly exist? What do you think, Hylas? Berkeley would applaud you; according to his philosophy, you have common sense. But a man of many talents is one thing, and a pedant is another. You make certain traces in the brain to be the causes or occasions of our ideas. Hyl: I think I understand you very clearly; and I admit that the proof you give of a Deity is as convincing as it is surprising. He builds on the most abstract general ideas, which I entirely disclaim. AND, from the variety, order, and manner of these, I conclude THE AUTHOR OF THEM TO BE WISE, POWERFUL, AND GOOD, BEYOND COMPREHENSION.

Next

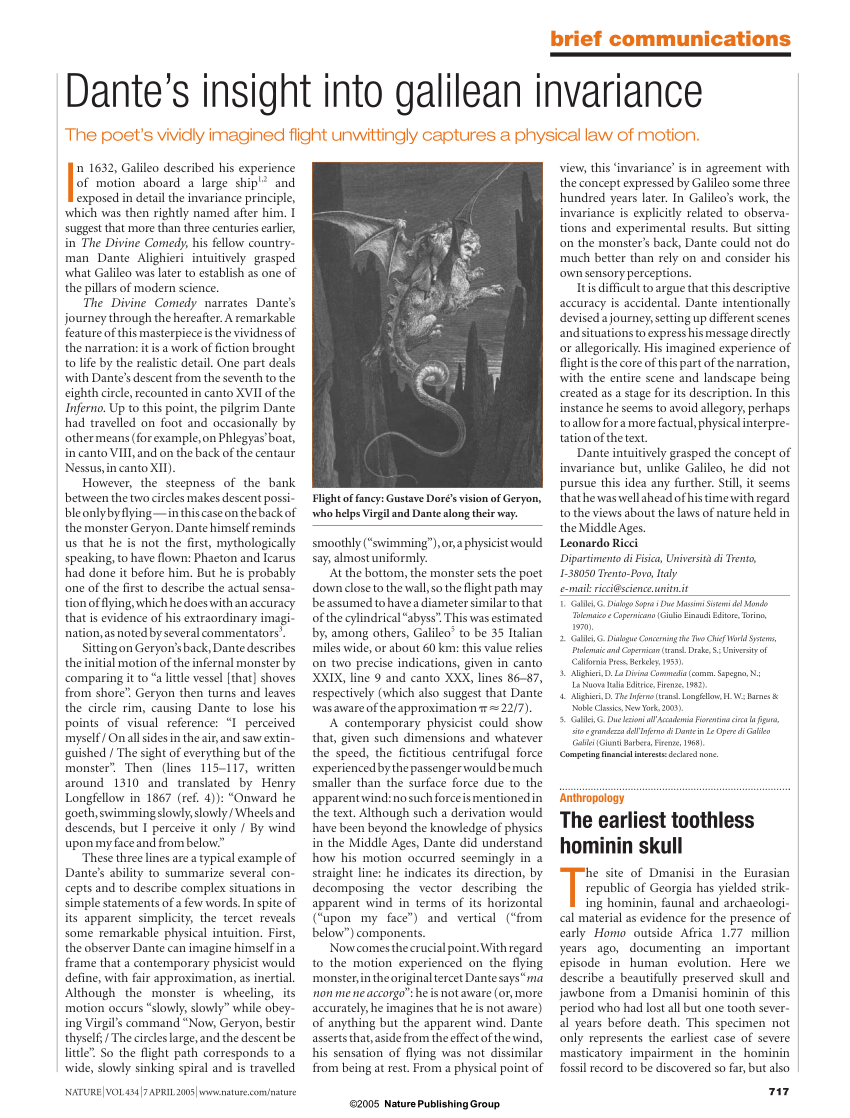

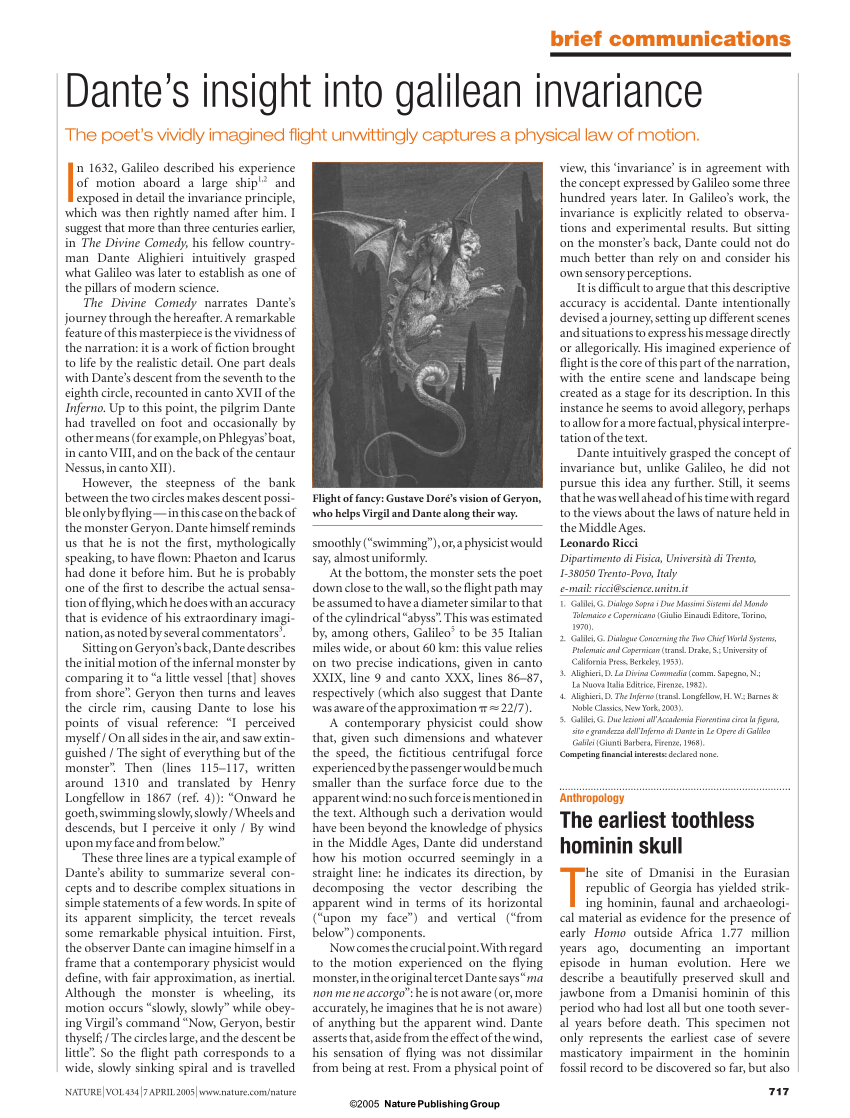

George Berkeley: Second Dialogue Between Hylas and Philonous

So Matter comes to nothing. I would by no means be thought to deny that God, or an infinite Spirit, is the Supreme Cause of all things. You are not, therefore, to expect I should prove a repugnancy between ideas, where there are no ideas; or the impossibility of Matter taken in an UNKNOWN sense, that is, no sense at all. Do you not at length perceive that in all these different acceptations of MATTER, you have been only supposing you know not what, for no manner of reason, and to no kind of use? Is there any more in it than what a little observation in our own minds, and that which passeth in them, not only enables us to conceive, but also obliges us to acknowledge. But do you not think it looks very like a notion entertained by some eminent moderns, of SEEING ALL THINGS IN GOD? It is supposed the soul makes her residence in some part of the brain, from which the nerves take their rise, and are thence extended to all parts of the body; and that outward objects, by the different impressions they make on the organs of sense, communicate certain vibrative motions to the nerves; and these being filled with spirits propagate them to the brain or seat of the soul, which, according to the various impressions or traces thereby made in the brain, is variously affected with ideas. Upon a nice observation, I do not find I have any positive notion or meaning at all.

Next

Berkeley's 'Three Dialogues': A Reader's Guide: Reader's Guides Aaron Garrett Continuum

Berkeley believes that an objective reality does not exist because of issues that come with materialism. So that upon the whole there are no Principles more fundamentally opposite than his and mine. As to the first point: by OCCASION I mean an inactive unthinking being, at the presence whereof God excites ideas in our minds. I deny that I agreed with you in those notions that led to Scepticism. Or, how often must it be proved not to exist, before you are content to part with it? You have already pleaded for each of these, shifting your notions, and making Matter to appear sometimes in one shape, then in another. For him, this explanatory gap set the limits of knowledge. Leave nature absolutely free to work her own way, and all will be well.

Next

Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous Second Dialogue 208

So matter cannot be the cause of our ideas. The things, I say, immediately perceived are ideas or sensations, call them which you will. Is it not common to all instruments, that they are applied to the doing those things only which cannot be performed by the mere act of our wills? But to fix on some particular thing. And, if Matter, in such a sense, be proved impossible, may it not be thought with good grounds absolutely impossible? But once the root has been plucked up, all its offspring will wither and decay as a matter of course. Here Alciphron, turning to Lysicles, said he could make the point very clear, if Euphranor had any notion of painting.

Next

Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous Second Dialogue 210

But I am not ashamed to own my ignorance. And what you have offered hath been disapproved and rejected by yourself. Reason is the same at all times and places, and when it is used properly it will lead to the same conclusions. I would by no means be thought to deny that God, or an infinite Spirit, is the Supreme Cause of all things. It seems then you include in your present notion of Matter nothing but the general abstract idea of entity.

Next

6.6: George Berkeley: Second Dialogue Between Hylas and Philonous

But what else is this than to play with words, and run into that very fault you just now condemned with so much reason? I would gladly know that opinion: pray explain it to me. May we not admit a subordinate and limited cause of our ideas? But still, methinks, I have some confused perception that there is such a thing as MATTER. Or is there anything so barefacedly groundless and unreasonable to be met with even in the lowest of common conversation? All I contend for is, that, subordinate to the Supreme Agent, there is a cause of a limited and inferior nature, which CONCURS in the production of our ideas, not by any act of will, or spiritual efficiency, but by that kind of action which belongs to Matter, viz. Proceed then to the second point, and assign some reason why we should allow an existence to this inactive, unthinking, unknown thing. In truth this is not fair dealing in you, still to suppose the being of that which you have so often acknowledged to have no being. I agree with you.

Next

3.2: Second Dialogue

But what say you? Tell me, Hylas, hath every one a liberty to change the current proper signification attached to a common name in any language? I would first know whether I rightly understand your hypothesis. But, not to insist on reasons for believing, you will not so much as let me know WHAT IT IS you would have me believe; since you say you have no manner of notion of it. When a repugnancy is demonstrated between the ideas comprehended in its definition. I do not expect you should define exactly the nature of that unknown being. Philonous explains that he is not a skeptic, because he did not begin with the false materialist premise, namely, that "real existence" is synonymous with "absolute existence outside of the mind". No; there is need of time and pains: the attention must be awakened and detained by a frequent repetition of the same thing placed oft in the same, oft in different lights. Other men may think as they please; but for your part you have nothing to reproach me with.

Next

Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous: Summary

It is to me a sufficient reason not to believe the existence of anything, if I see no reason for believing it. Phil: But what if it should turn out that even the most general notion of instrument, understood as meaning something distinct from cause, contains something that makes the use of an instrument inconsistent with the divine attributes? Since you will not tell me where it exists, be pleased to inform me after what manner you suppose it to exist, or what you mean by its EXISTENCE? May we not admit a subordinate and limited cause of our ideas? No; I should think it very absurd. How sincere a pleasure is it to behold the natural beauties of the earth! In fact, he goes so far as to say that your commitment to this belief runs counter to common sense. But, where there is nothing of all this; where neither reason nor revelation induces us to believe the existence of a thing; where we have not even a relative notion of it; where an abstraction is made from perceiving and being perceived, from Spirit and idea: lastly, where there is not so much as the most inadequate or faint idea pretended to—I will not indeed thence conclude against the reality of any notion, or existence of anything; but my inference shall be, that you mean nothing at all; that you employ words to no manner of purpose, without any design or signification whatsoever. Poverty is relieved, ingenuity is rewarded, the money stays at home. From reflecting on and thinking about these facts, thoughtful men have concluded that all religions are false—are fables.

Next

Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous Second Dialogue 215

And have not you acknowledged, over and over, that you have seen evident reason for denying the possibility of such a substance? Truth and beauty are in this alike, that the strictest survey sets them both off to advantage; while the false lustre of error and disguise cannot endure being reviewed, or too nearly inspected. And, though it should be allowed to exist, yet how can that which is INACTIVE be a CAUSE; or that which is UNTHINKING be a CAUSE OF THOUGHT? And, when you have shewn in what sense you understand occasion, pray, in the next place, be pleased to shew me what reason induceth you to believe there is such an occasion of our ideas? Sensible things are all immediately perceivable; and those things which are immediately perceivable are ideas; and these exist only in the mind. Hyl: But I could never have seen it as being so empty as it now seems to be! Through the motion of particles, goes the usual theory, matter somehow stimulates us and gives rise to our ideas. Phil: An instrument, you say. But even if you are right about what is convenient or helpful, how does that prove these ·moral· notions to be true? The reality of things! Upon the whole, I am content to own the existence of matter is highly improbable; but the direct and absolute impossibility of it does not appear to me. Those philosophers seem to have been predecessors of those who are now called free-thinkers.

Next

4.1: First and Second Dialogues

This provides you with a direct and immediate proof, from a most evident premise, of the existence of a God. In this process of question and answer, if a man makes a slip is he allowed to recover? Even in rocks and deserts is there not an agreeable wildness? I am perfectly at a loss what to think, this notion of OCCASION seeming now altogether as groundless as the rest. He maintains that we are deceived by our senses, and, know not the real natures or the true forms and figures of extended beings; of all which I hold the direct contrary. Or, of that which is invisible, that any visible things, or, in general of anything which is imperceptible, that a perceptible exists? You agree that the things immediately perceived by sense exist nowhere outside the mind; but everything that is perceived by sense is perceived immediately; therefore there is nothing sensible ·or perceivable· that exists outside the mind. He builds on the most abstract general ideas, which I entirely disclaim.

Next