Santoka Taneda was a Japanese Zen Buddhist poet who is known for his haiku poems, which often featured themes of nature and the impermanence of life. Born in 1882 in the Fukui Prefecture of Japan, Taneda was orphaned at a young age and was raised by his grandparents. He later left home and traveled throughout Japan, living a nomadic lifestyle and practicing Zen Buddhism.

Taneda's poetry reflects his spiritual beliefs and his experiences as a wanderer. Many of his haiku poems depict the natural world and the fleeting moments of beauty that can be found in it. For example, one of his most famous haiku reads: "Over the wintry / Forest, winds howl in rage / With no leaves to blow." This poem captures the raw, elemental power of nature and the impermanence of all things, as the winds howl through a barren forest in the depths of winter.

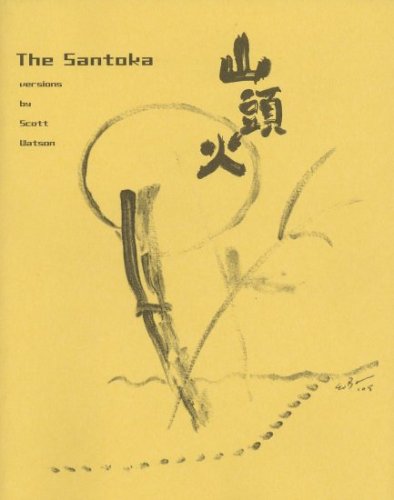

In addition to his poetry, Taneda is also known for his calligraphy, which he used as a way to express his spiritual beliefs and to connect with the natural world. His calligraphy was characterized by its bold, expressive strokes and its emphasis on the visual beauty of the characters.

Despite his fame as a poet and calligrapher, Taneda lived a simple and humble life, often relying on the generosity of others to support himself. He died in 1940 at the age of 58, but his poetry and calligraphy continue to be admired and studied by people around the world.

In conclusion, Santoka Taneda was a Japanese Zen Buddhist poet and calligrapher who used his art to express his spiritual beliefs and to connect with the natural world. His haiku poems and calligraphy continue to be admired and studied by people around the world.

Santoka Taneda Haiku and Quotes

This coincided with the beginning of the Russo-Japanese war in 1904. He began to drink again and run up large bar tabs and the cycle of self-destruction resumed, thus also financially ruining him and his wife's bookstore business. The name is originally one of the list of natchin Santōka is unrelated to the actual year in which the poet was born. His father had continued to squander the family wealth on women and sold pieces of land to pay the bills. Many of these stories to me, though I am certain are true, seem to fall into a sort of traditional folklore about poet priests that were established before Santoka's time by Saigyo, Ikkyu and Ryokan, thus laying the groundwork for Santoka to become a folklore hero. In order to do that we need to be mindful of our meal, really chew our food, take the time to find its flavor, focus on the taste, the texture, the warmth of the rice. Again it may have been Shiki who paved the way for this to be a common topic to put in one's notebook.

Taneda Santoka Poems > My poetic side

Here are some haiku by Santoka: no sake i stare at the moon drunk i slept with crickets sometimes the sound of swallowing sake seems very lonely For fun here is one by Kerouac: missing a kick at the ice box door it closed anyway On a very interesting note another topic Santoka wrote about was pure cold water. That year several of his friends also renovated an old hermitage for Santoka, which he named "Gochuan," or "Cottage in the Midst. They can be understood at once without analysis. Shiki writes: autumn passes for me no gods no buddhas autumn wind gods, buddha lies, lies, lies Now one from Santoka: all day long meeting demons meeting buddhas Following the theme of life, there of course is a central theme of death for Santoka. These were very hard miles, miles which brought sun and rain, generosity and hostility, food and hunger, smiles and scowls, health and illness, thirst and pure water, loneliness and moments of companionship, grief and intense happiness, but moments always lived with the thought that everything should be welcomed, whether good or bad. This seeing though in Buddhism is not an easy thing to do; it is the same with eating.

Santoka Taneda (1882

We recall Issa's famous haiku: the world of dew the world of dew it is indeed and yet and yet. Blyth writes: Santoka put every ounce of his spiritual energy into his verses. Sometimes too he would get so drunk that he would land himself in jail, which takes a lot of skill in Japan, because of their tolerance, or he would not be able to pay his bill and would tell the police to go to the person's house he was staying at and that they would pay for him. Does the person's colorful life enhance or diminish the author's work? For All My Walking. There was a problem getting your location. Taneda Santoka was born in 1882 and died in 1940. He like Santoka was a poet priest, but in the Pure Land tradition, not in the Zen.

Taneda Santoka Critical Essays

By being aware of the natural beauty that surrounds them, they become closer to all that is in the universe, thus elevating themselves in some type of Eastern Petrachian enlightenment. Continuing with this request will add an alert to the cemetery page and any new volunteers will have the opportunity to fulfill your request. In April 1911 Seisensui established the magazine Sōun to expound the theory that it is necessary for a poet to express what is in his heart in his own language without regard to any fixed form. Instead it opted for a freer verse form. But as we can guess his ghosts were only in remission. Running around drinking in this messy way—utterly stupid! His haiku are generally bare, as I said before. You might get caught in a shower, but I would guess you are probably writing from inside a cozy house.