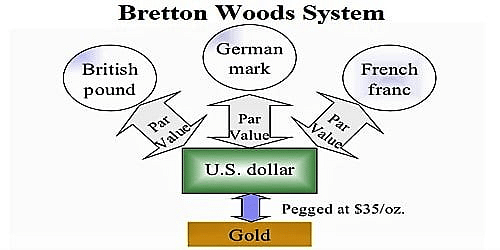

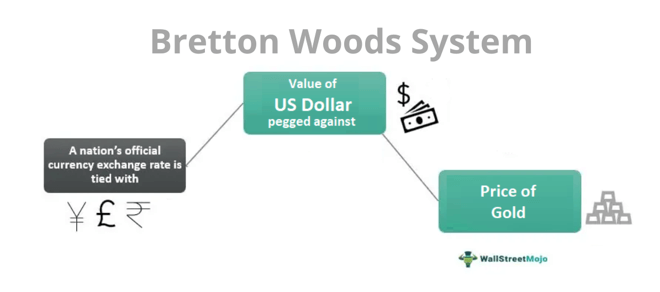

The Bretton Woods system was a monetary order established at the end of World War II that pegged the value of major currencies to the price of gold, with the U.S. dollar serving as the reserve currency. This system aimed to promote international economic stability and cooperation by establishing fixed exchange rates between currencies, with central banks committing to buy and sell their currencies at these fixed rates.

However, this system ultimately collapsed in the 1970s due to a combination of internal and external pressures.

One of the main internal pressures on the Bretton Woods system was the increasing difficulty of maintaining the fixed exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and gold. The U.S. had committed to maintaining the value of the dollar at $35 per ounce of gold, but rising costs and inflation made it increasingly difficult to keep the dollar at this value. To maintain the value of the dollar, the U.S. had to run trade surpluses and maintain low levels of inflation, which became increasingly difficult as the U.S. economy expanded and the costs of the Vietnam War put pressure on the budget.

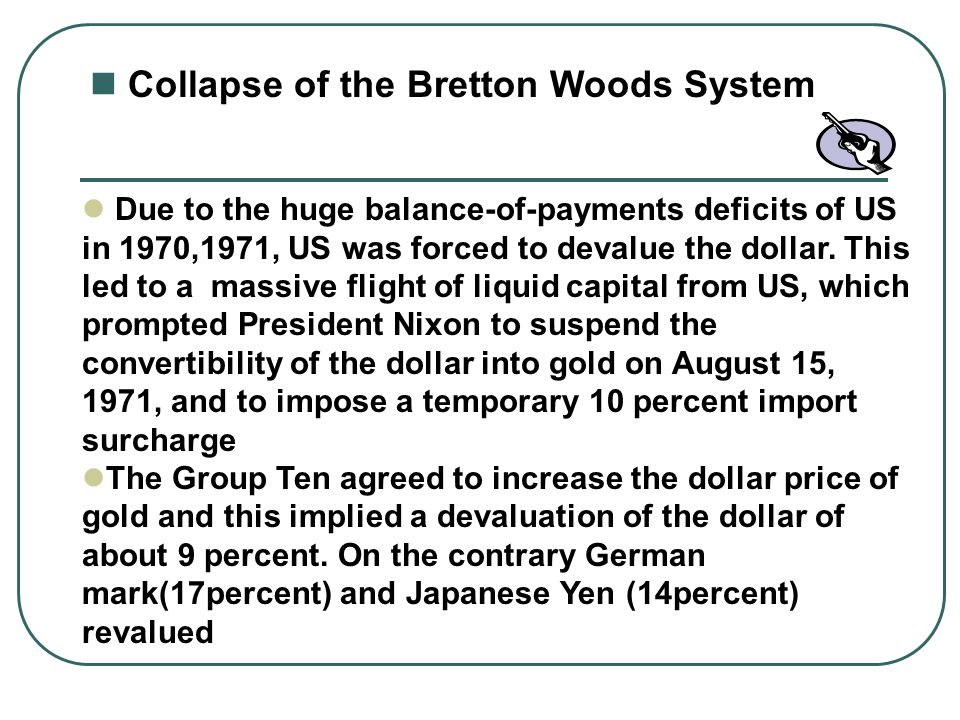

External pressures also contributed to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. The growing strength of other economies, such as Germany and Japan, made it more difficult for the U.S. to maintain its dominant position in the global economy. These countries began to accumulate large trade surpluses, which put pressure on the U.S. to buy more of their currencies to maintain the fixed exchange rates. This put further strain on the U.S. dollar and made it more difficult to maintain the value of the currency.

Additionally, the rising cost of the Vietnam War and other domestic spending put pressure on the U.S. budget and led to the printing of more money, which contributed to inflation and further eroded the value of the dollar. As a result, other countries began to lose confidence in the U.S. dollar and the stability of the Bretton Woods system.

In 1971, the U.S. suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system. This event, known as the Nixon Shock, marked the end of the fixed exchange rate system and the beginning of the floating exchange rate system that is in use today.

Overall, the collapse of the Bretton Woods system was due to a combination of internal and external pressures that made it increasingly difficult to maintain the fixed exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and gold. The system's collapse marked the end of an era of fixed exchange rates and the beginning of the floating exchange rate system that is in use today.